These days, if you read a magazine article or newspaper story that contains the words ‘graffiti’ and ‘church’ in the same sentence then it is unlikely to have a happy ending. Graffiti has become a word associated with vandalism and destruction. Why then should we study graffiti?

If you enter one of the many hundreds of surviving medieval churches that can be found in the county of Norfolk just about everything you see will relate to the elite members of the medieval parish; the top 5% or so. The stained glass, alabaster tombs and monumental brasses tell us only about those who created them or caused them to be created. They tell a story of power and riches.

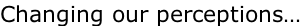

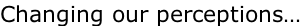

The coloured glass of the medieval church window, and the dull brasses laid into marble upon the floor, do not carry images of peasants ploughing - but of the local gentry in all their finery. Where here is the voice of those who worked the parish land, who worshipped in this splendid monument to their betters, who laboured to build it? Graffiti can be, and was, created by all levels of society and it offers a unique and un-studied insight into the people of the medieval parish. The graffiti can offer a voice to the lost population of the medieval world.

The study of medieval graffiti is also changing the way we think about how the inside of the medieval parish church may have looked during the middle ages.

Today medieval graffiti is actually quite hard to find without the use of angled light sources and a great deal of time. Even examples inscribed in quite prominent positions are often hard to see with the naked eye. A few faint lines scratched in the stonework. However, that would not have been the case during the middle ages.

The interior of a medieval church would have been a place of vibrant colour and paintwork. In particular, the lower sections of the wall, which were unsuitable for elaborate painted images, were often coloured with a single pigment. Reds, deep orange ochres and blacks were all relatively common—and it is in these areas that we often find graffiti inscriptions. Therefore, far from being hidden away, the graffiti would have been very obvious indeed, scratched through the pigment to reveal the pale stone beneath.

In some churches these inscriptions appear to deliberately avoid crossing over other inscriptions, even in very busy areas of the church, suggesting that they respected the earlier graffiti and were unwilling to destroy it. The result would have been a medieval church literally covered in pale inscriptions etched through the paintwork. The very fact that these inscriptions were tolerated, and even seen as part of the normal use of the church fabric, changes our view of how the inside of the medieval church may have looked.